Written by Chay Bacani-Florencio

Vichea Long is a 45-year-old Cambodian with a blind eye and a fully amputated right arm, multiple disabilities that he acquired during his service as a Cambodian border police officer. Afterwards, regular employment options became scarcer. In the hopes of simply providing for his wife and small children, he decided to take a chance on migrating to Thailand for work as a farmer.

With the assistance of a recruiter recommended by a relative, Vichea Long brought his wife and children to Thailand without going through any application process or medical examination. He, along with a group of other undocumented Cambodians, was promised that a passport and visa would not be necessary, and that assured employment was just twenty kilometres from the border. In 2004, Vichea and his family walked for half a day from their home in Cambodia to reach the sugar cane farm in Thailand.

The Lack of Labour Protections

On the farm, Vichea Long worked ten hours a day, seven days a week. He was paid based on the weight of the produce that he was able to harvest, but his disability impacted his work, as he only received half of the pay that the other farmers earned. With delays in the payment of his wages and excessive deductions made for the food they consumed, it was often the case that the little money that was left was not sufficient to send any to his parents back home.

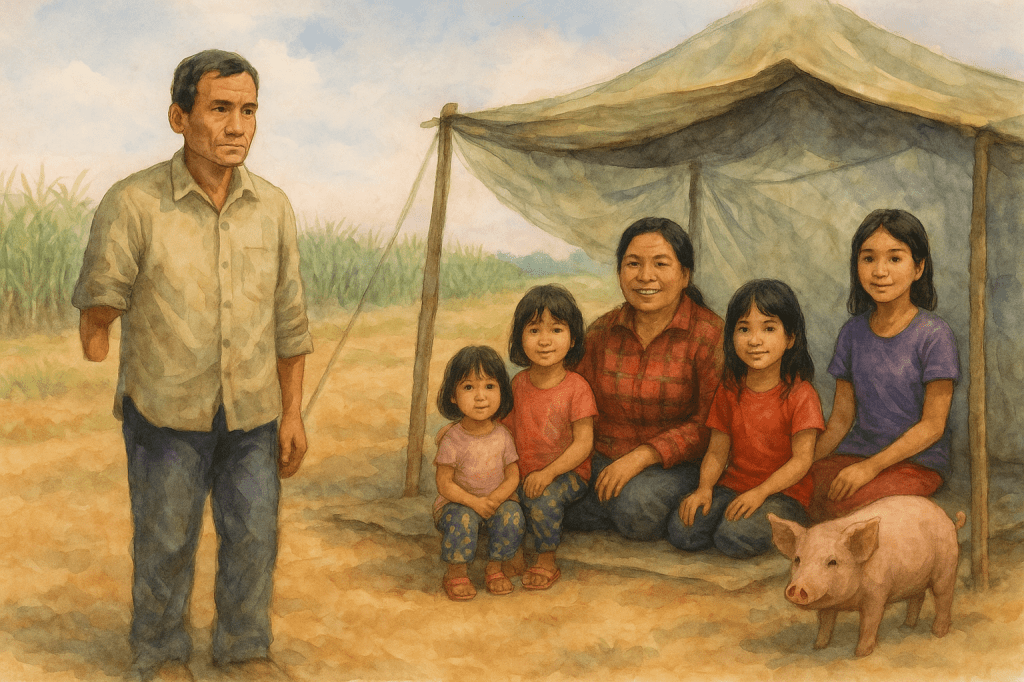

Each time the harvest ended, he and the other migrant workers relocated to another farm with the assistance of their recruiter. Once they were hired, the farmers wouldn’t have any contact with their recruiter, leaving them unable to bargain over wages or their work conditions. This precarious arrangement made Vichea Long’s work unstable and living conditions unbearable. Given the impermanence of employment, and without a room or a proper tent provided, he and his family were forced to install a mosquito net on their designated farm and sleep on bare ground.

When Extortion Becomes the Norm

Vichea Long was apprehended twice by the Cambodian and Thai border police. Without proper identification and documentation, he was forced to appeal his case. Money was demanded both times. While it was customary to pay Thai Baht 100 (US$ 3), he pleaded that he earns less than most workers because of his disability. The amount was reduced to Thai Baht 50 (US $1.50), reflecting the systemic normalisation of extortion.

Returning Home to Insufficient Support

After two years in Thailand, Vichea Long decided to return with his family to Cambodia. The family again crossed the border on foot and rode a taxi home, paying for their fees out of his pocket. Yet, life remained difficult with so many workers competing on so little land to till.

Only in 2024, when he met an organisation devoted to the cause of police officers who have sustained injuries, was Vichea Long able to receive reintegration assistance, more than two decades after he acquired his disability. There was a promise of an initial US$ 250 and US$ 15 a month thereafter. However, he has not received anything, only a few pigs, which he requested to sustain his livelihood.

Vichea Long’s experience as a farmer with multiple disabilities abroad reveals the exploitative work conditions that undocumented migrant workers are forced to live with. This results in a more impoverished situation for those with disabilities whose vulnerability is heightened when confronted with unsafe migration pathways, wage discrimination, and unlivable accommodations that are unchallenged for far too long. Migrant workers with disabilities should be entitled to accessible, affordable, and legal recruitment channels. It is just for them to also call for a fair wage system and labour protections. Adequate as well as immediate programmes for their reintegration into the community should also be given utmost priority.

Images generated with assistance of OpenAI, images conceptualized and final edit by Ferdinand Paraan Jr.