Written by Chay Bacani-Florencio

Sreyna Chan is a 35-year-old Cambodian national with a mobility impairment since she was nearly one year old. As the eldest, this did not stop her from providing for her seven siblings. However, living in Cambodia prevented her from being hired, as it denied her access to stable and inclusive employment, given that her disability is visible. At 19, she decided to migrate to Thailand to secure a stable employment that would provide for her family.

Escaping Exploitative Work Conditions, Crossing Borders

Sreyna Chan began her journey as a migrant worker in Thailand through irregular channels, yet she was not spared from discrimination. She experienced name-calling from fellow Cambodians, and it was directed at her disability. Still, she chose to endure in silence and focus instead on work to support her siblings.

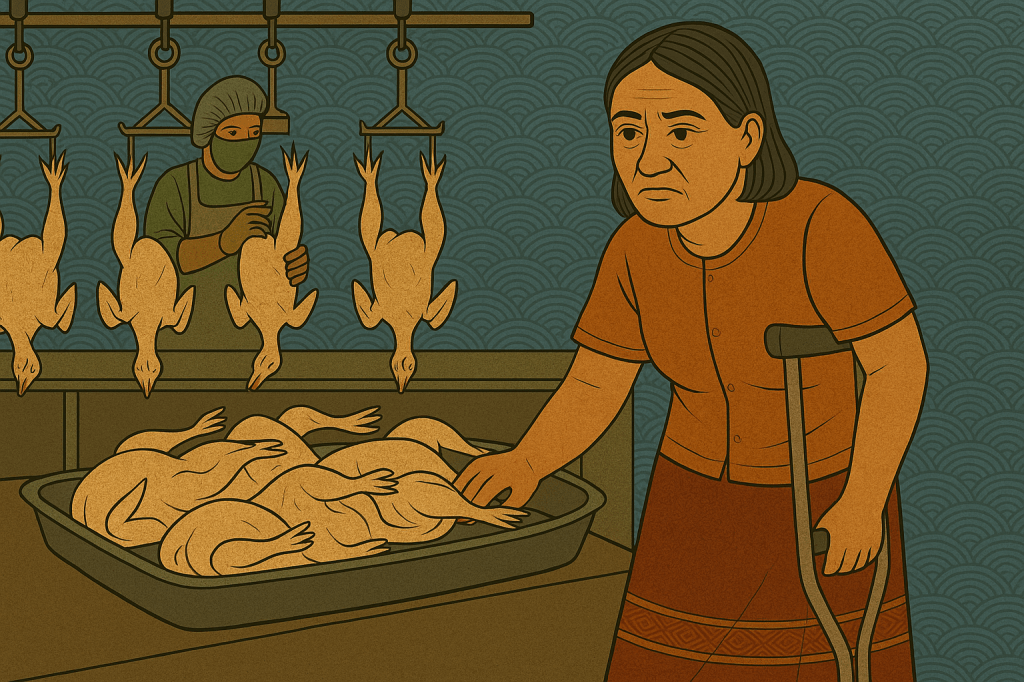

For her first job at a chicken processing factory, she signed a contract both in Khmer and in Thai; for the latter, she used her employer’s translator, whom she had no choice but to trust as she could not read Thai. It was in this job that she experienced extreme cold, which made the environment physically unsuitable. Despite being favoured by her supervisors, her passport was kept until she paid off her debt, which she never achieved. Due to health concerns and without access to formal complaint mechanisms, she was forced to escape the job without formally resigning and returned back to Cambodia.

Later, she returned to Thailand and found work in another factory. Once again, her passport was withheld, binding her to exploitative conditions, including low wages and the denial of overtime pay. Again she felt that she had to escape, so she went back home to Cambodia.

She procured a new passport for her third return to Thailand when she worked as a cleaner in a furniture manufacturing factory. It was there where she was exposed daily to dust and hazardous materials from the wood cutting process. When the company began downsizing, she felt she had no choice but to leave and return to Cambodia without her passport, before she’s let go.

Sreyna Chan endured her fourth and final stint as a migrant worker in Thailand, ending the familiar cycle of renewing passports and returning home, at a plastic manufacturing factory, this time alongside her younger sibling. Living with a physical disability, she was placed in a job that failed to accommodate her needs and imposed exhausting, irregular hours. Graveyard shifts often stretched into daytime work, depriving her of adequate rest and disrupting her sleep cycle. Over time, the toll on her body became undeniable, and she began fainting as often as twice a month. Yet, without access to proper labour protections or disability accommodations, and driven by financial necessity, she felt she had no choice but to keep working.

Extortion and Escape

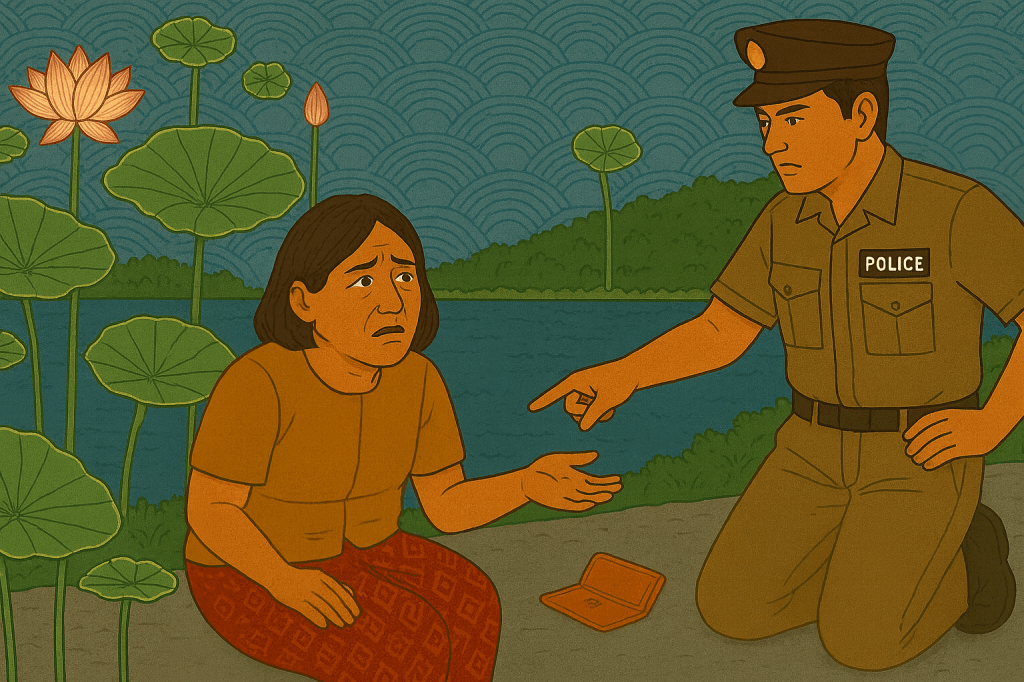

Without a viable way out of unjust work environments and restrictive contracts, Sreyna Chan had no choice but to leave. Leaving meant not just escaping her employers and piled-up work-related debt. She also had to navigate the authorities. During her first employment in Thailand, Syrena Chan left the factory. She was arrested near the border and asked for a fine, which, if she could not pay, would lead her to be transported to an abandoned area without any access to help.

Fearing for her safety, she paid what little she could. Even then, she was transported to a forested area with 20 other immigrants, and they were instructed to scatter and look for the road where a blue bus would eventually pick them up and drop them off at the border. Still without a passport, terrified, and physically strained to walk long distances by herself, she hired someone to assist her in crossing the border to safety.

Reflections on a Migrant Worker’s Vicious Cycle

Amidst more than a decade of being a migrant worker in Thailand, Sreyna Chan endured the vicious cycle of escaping hazardous work conditions, evading a fixed-term work contract, turning to irregular and dangerous routes returning home, and repeatedly acquiring new passports just to re-enter the same exploitative conditions. Restricting her freedom to choose fair and just labour conditions not only puts persons with disabilities such as her at heightened risks but also undermines their right to freedom of movement and access to justice.

Images generated with assistance of OpenAI, images conceptualized and final edit by Ferdinand Paraan Jr.