Written by Chay Bacani-Florencio

Rathana Heng, a 51 year-old Cambodian has striven to provide for family despite acquiring his disability when he stepped on a landmine in 2003, amputating one foot in the process. Daily wages in his country then were as low as KHR 6,000 (US$ 1.50) a day, far insufficient to support his widowed mother and younger siblings. In 2008, he was approached by a broker who offered him assured employment in a construction site in Thailand that would overlook his disability, with the promise of a higher pay.

From Worker to Captive

The broker did not inform Rathana Heng of the expenses needed for migrating to Thailand. He was simply asked to walk the whole day traversing the mountainous borders and was instructed to wait for a truck to take him and his fellow prospective migrant workers to their employer. About thirty workers were piled into the truck with him, unable to move, and taken to where they were told to wait before formally starting work. It turned out that the job awaiting him was not a construction role, but that of a worker on a fishing boat.

While his employer assisted with his passport, it was withheld. No contracts were ever written up either, and no verbal agreement about the wages was communicated. He was kept at sea for approximately two years without docking. The boat he worked on was unlicensed, hence, instead of returning to land, other fishing vessels would just approach them to offload their catch, and additionally the migrant fishermen like him were forced to transfer from one boat to another, as they were being moved to evade inspections. Whenever authorities approached their vessel, they were ordered to hide (it was unclear if everyone hid or just some).

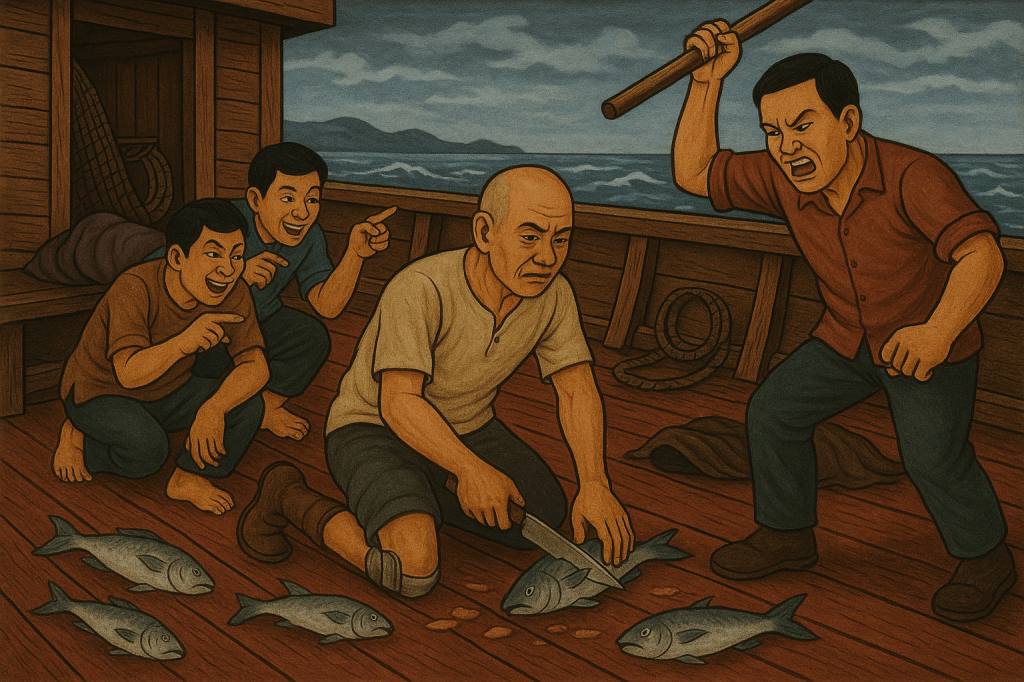

Bullied and Beaten

Rathana Heng recalled not having any fixed working days and hours, working 7 days a week. They were fed only twice a day, which was often insufficient and left them hungry. There was only one rule, and that was to finish cutting fish from evening until morning. If he did not accomplish this, he would be beaten up by the boat’s owner or supervisor. He never received his wages, and he was only allowed to borrow Thai Baht 8,000 (US$ 245) that was expected to be repaid to the boat owner. This was used prior to departure to purchase personal supplies.

Being the only worker with a disability, he was the target of discrimination. Other migrant workers ridiculed his prosthetic leg, as he had difficulty carrying heavy loads, and at times they threw things mockingly at his head. When he would request for a break, he would get denied and was demanded to work like the others (persons without disabilities).

One harrowing incident broke Rathana Heng’s spirit. A Myanmar worker was struck on the head by the boat’s hook and died instantly. While they were told to stop work and rest below deck, they did not reach land, and their co-worker’s body disappeared.

The Costs of Escape

Out of desperation to have his mental health treated, Rathana Heng thought of seeking help from the authorities. When their boat was stopped by the Taiwanese Police, he almost approached them to plead for assistance. However, his co-worker warned him that they would not take him to seek medical care, and that he would be brought in for something else, which frightened him and stopped him from surrendering. Later, when being transferred to another boat, he agreed with the captain that he (and a friend) would be free to leave the boat once they reached the shore the next time. He paid THB 6,000 (US$ 183) to the captain and after that, he was free to go. When he approached the Thai police, he expected that they would arrest and deport him. However, he was met with indifference and was provided with no support. Instead, he walked home towards the Cambodian border and survived by collecting coconuts until he encountered Cambodian workers who helped him get home. After three years of surviving forced labor at sea, Rathana Heng was able to return to Cambodia. He vowed to never migrate again.

Life Back in Cambodia

Back home, Rathana Heng’s functioning worsened. He now suffers from continuous headaches but initially had no access to affordable health care, and his physical and psychosocial afflictions were untreated. In 2024, after much initiative and research, he was able to join various community outreach and training programs. He received a prosthetic foot from a non-government organization and a disability card from the government with the help of an Organisation of Persons with Disabilities (OPD). Despite this, he feels that state support remains limited. Rathana Heng runs a small business with support from a local civil society organisation, yet income remains unstable, leaving him feeling insecure and judged by relatives who assumed that migrant workers like him obtained high paying jobs abroad.

Rathana Heng’s migration story demonstrates overlapping human rights and labour standards violations. As a victim of trafficking, he was forced to work on different fishing boats, while being unpaid, beaten, deprived of adequate food and rest. Overworked and abandoned, he was deceived into the promise of opportunity while being unwillingly marooned at sea.

The often invisible struggles of undocumented fisher folk as reflected in Rathana Heng’s story of concealed exploitative practices, suggests the need to call for stronger protections in the fishing industry. This is heightened for the vulnerabilities of migrant workers with disabilities like him who were beaten and mocked due to discrimination. The impact of such traumatic events are aggravated by the denial of justice that could have been prevented with strengthened cross-border protections through informed and acknowledged rights and accessible complaint mechanisms.

Images generated with assistance of OpenAI, images conceptualized and final edit by Ferdinand Paraan Jr.