Written by Chay Bacani-Florencio

Miguel Rivera, a 49-year-old migrant worker from the Philippines, was born with an undiagnosed congenital cataract in his left eye, resulting in visual impairment. His career in the local fast food industry in the Philippines spanned 16 years, starting as a server and later gradually rising to a managerial position. In 2017, as his eldest child was about to enter college, he decided to start looking for work abroad in the hopes of better supporting his family’s needs.

Barriers to Equal Opportunity and the Right to Work

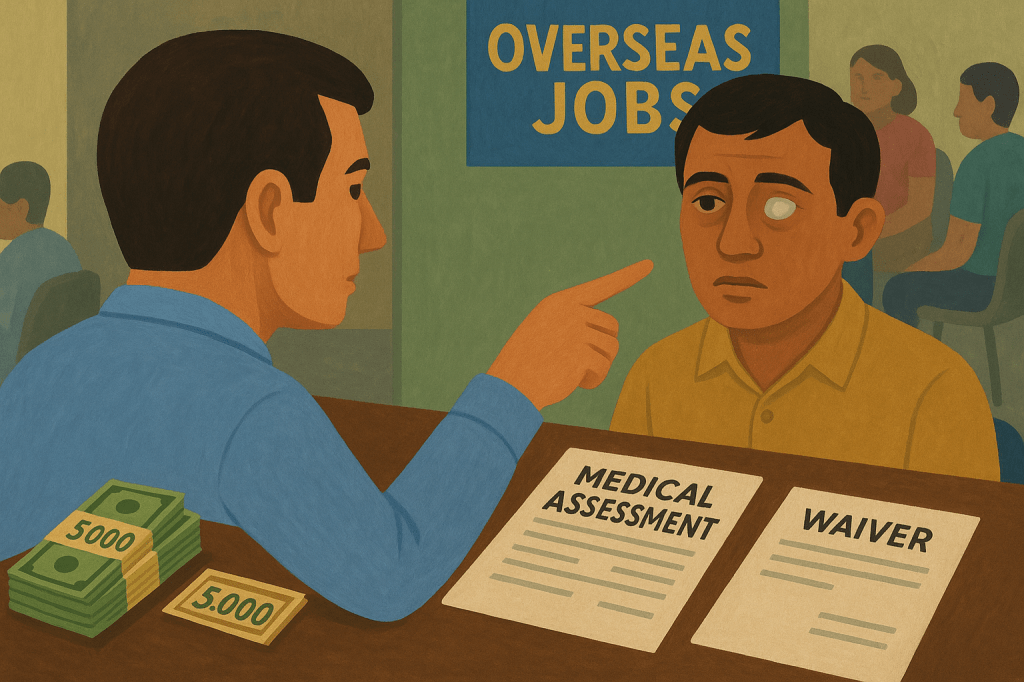

Through an online recruitment agency, he made an application as a restaurant manager in Saudi Arabia. Despite the swift and successful initial interview his preliminary physical assessment noted a concern with his eyesight, the application was obstructed. The recruitment agency required a second opinion from a private hospital where his congenital cataract was formally diagnosed, costing him nearly 5,000 PHP (US$ 80). The agency required a special waiver letter from his prospective employer to confirm their willingness to hire a person with a disability. It was provided, and after a three-week delay, his employment was pushed through. The rest of the procedures were paid by the agency and later taken out of his wages.

Upon departure from the Philippines, Miguel was unprepared to face mandatory deductibles. He was obliged by the Philippine government to pay social security and healthcare insurances, and it was not clear to him how these could be used while overseas. The process of paying itself proved inconvenient, as one had to go to the bank and line up for payments, which required days off work.

Navigating the Reality of Isolation

Miguel’s pre-employment experience in the Philippines proved to be a temporary obstacle upon arriving in Saudi Arabia. His employer not only immediately hired him but also entrusted him with the responsibility of interviewing and building his team of seven Filipinos, in addition to other Indian, Nepalese, and Sudanese co-workers. The employer also allowed Miguel and his new team to set up their own living spaces, as they were free to purchase their toiletries, beddings, and other personal effects.

However, despite his professional success, Miguel still experienced social isolation and challenges of integration that many migrants face. Burdened with having to adapt to the language and culture by himself during his first year in Saudi Arabia, he experienced periods of loneliness leading to depression. Plus, the demands of his job and the differing schedules of his colleagues, combined with the remote location of the restaurant, made it difficult to build social connections and engage in community life. This highlights how the challenges of isolation and adapting to a foreign environment can place migrant workers at risk of developing psychosocial disabilities. While depression does not always constitute such a disability, in some cases it can lead to or overlap with one, particularly when left unaddressed.

The Call for Disability-inclusive Employment Back Home

Miguel would return to the Philippines every two years for his vacation days. The airfare would always be paid for by his employers. However, his overseas journey concluded with his return to the Philippines in 2021. The rising costs of the pandemic forced him to accept that his wage was no longer enough to sustain a life abroad while sending money to his family back home. Upon his return, he received financial assistance from the Overseas Workers’ Welfare Association’s (OWWA) programme. He also had procured a Person with Disability ID and was able to receive benefits according to his status.

Providing for his family back home proved challenging as his efforts to find a job were met with a new form of discrimination. When applying for a manager position at a local hotel, the recruiter questioned discouragingly whether he wanted to disclose his disability. Miguel feels that the social stigma is still strong for persons with disabilities, limiting the chances for fair opportunities to work and equitable sources of income.

Reintegration Support Also Means Right to Fair Work

Miguel hopes to take part and see a society that fully supports accessibility for returnee migrant workers with disabilities. His story calls for the need to strengthen government-led programs that promote the right to work of persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others. The additional layers of screening in the recruitment process signify administrative delays and financial burdens and extra costs carried by persons with disabilities. This situation underscores the failure to provide accessible support services and protection against disproportionate costs often incurred unnecessarily by persons with disabilities in the migration process.

Images generated with assistance of OpenAI, images conceptualized and final edit by Ferdinand Paraan Jr.