Written by Chay Bacani-Florencio

Mathida Win is a 50-year-old Myanmar national who was born with a condition that caused her legs to develop unevenly. She had undergone multiple surgeries throughout her childhood and early adulthood to reinforce her bones. When she turned 40 years old, she was recommended for another procedure. Unfortunately, due to financial constraints, she stalled the much needed surgery and is still walking with a limp. When her parents divorced at the age of 10, she lived with her mother’s relatives as her mother and sister migrated to Thailand to work as domestic workers. When her grandparents and aunt passed away, she stayed with other relatives. As she did not receive any support or financial assistance from the government, she survived only on the remittances received from her family in Thailand.

Unsafe Journeys Across Borders

Mathida Win initially did not migrate to work. Her mother and sister strongly discouraged her from working in Thailand because of her disability. She visited Thailand multiple times to visit her family. The first instance was in 2009 when she paid THB 1,000 (US$ 30), rode and hid inside the storage compartment of a double-decker bus to cross the border of Thailand. While she was not the only one hidden inside the vehicle, she recalled how the checkpoint authorities poked spears into the packages, injuring some in the process. On another occasion, while boarding a plane, her ID was taken by the authorities as she was suspected to illegally cross the border. She offered to leave her ring as a guarantee that she was merely going to see her mother and sister, who had her passport, but no one believed her. She was kept in a hotel room for three days, which she had to pay for herself, and pleaded with her mother and sister to wait for her to come to them, as she is ashamed to be a burden. They arranged her release with a broker, had her settle the payment, and allowed her to cross the Thai border. Without any money left, she didn’t consume anything, nor did she have water to drink. She was also too timid to ask for the bus to stop if she needed to use the restroom. She recalled how the Thai bus driver showed her sympathy upon seeing that she had a disability and gave her food to eat.

During a visit to Thailand, in 2012, Mathida Win was asked to come back to Myanmar to take care of her sick aunt. After her aunt’s death, she went back to Thailand and this time, with the help of her mother, was able to secure employment as a domestic worker. In 2017, her mother was diagnosed with cancer and decided to move back to Myanmar. At that time, she stayed in Thailand as a domestic worker until 2018 and moved back to her mother’s house. In 2019, she was referred by a relative who used to work for a foreign family living in Thailand. She secured the services of a broker, paid THB 23,500 (US$ 725), and migrated to Thailand. She arrived undocumented but later received a ‘Pink Card’, which provides her limited legal status.

Lack of Contract, Long Hours, and Low Pay

Mathda Win’s Day as a domestic worker usually starts at 6:00 AM. Her tasks include cleaning, ironing, laundry, running errands, assisting in the kitchen, and preparing meals. Her workday usually lasts until 11:00 PM. When the family has parties, she extends her hours up to 4:00 AM and resumes late the next day. And while an elevator is provided in the building of her employer’s residence, consisting of the 18th and 19th floors, she is expected to take the stairs in between those two floors, to which she recalls that she repeatedly does at least thirty times a day. And although there are other domestic workers within the same household to offer her assistance, she is still expected to carry the same grocery or shopping bags. She needs to take medication afterwards due to shoulder pains.

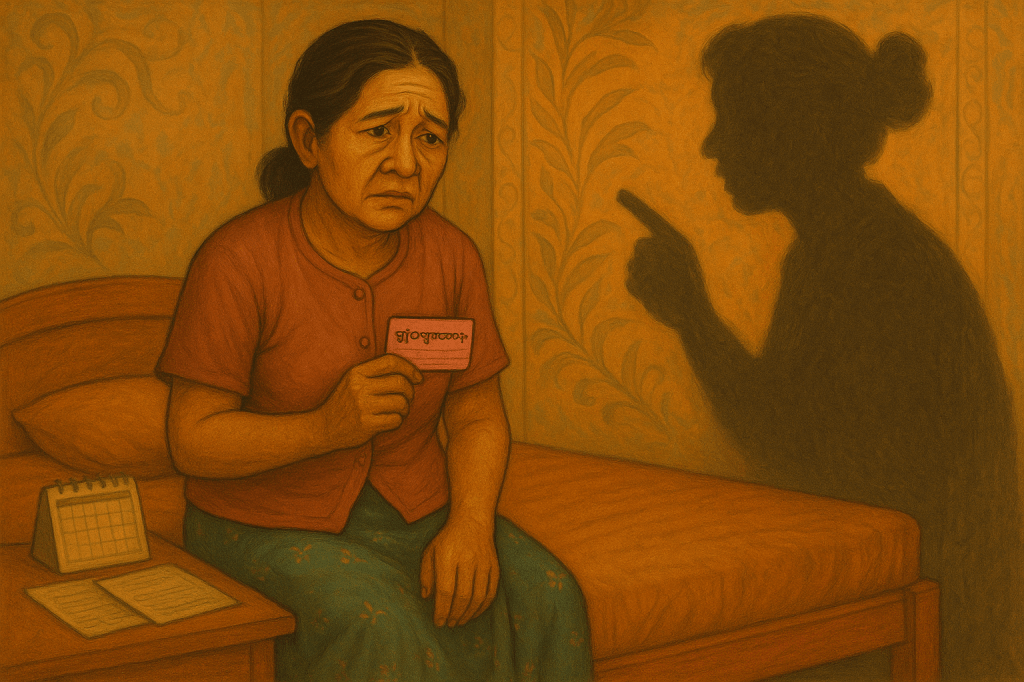

Mathida Win has been serving the family without a written contract. This made it easy for her to be let go and face unemployment. When the pandemic hit in 2020, the family returned home to their country of origin, and she became jobless. When they returned back to Thailand in 2022, they requested her services. However, when the family went abroad, she was again let go. It was only when the family’s children came back in 2023 that they asked for her again. She suffers some abusive behaviour from her employer as well, but she expressed that as she was a person with a disability, having ties with this family, and that this had been her only ever job, she believed she had no alternative options. They deduct her salary when something in the house is damaged or broken. She is ridden with anxiety whenever the employer’s wife loses her things, as she would be wrongfully accused of stealing, even though her innocence would be proven the next day. When this happens, she is also demanded to do additional errands on top of being already overburdened. And as if to hurry her up, she is sometimes physically pulled by her employer’s wife to look for her lost things.

Mathida Win feels that her low salary, heavy workload, and the maltreatment she faces are all due to how they perceived her disability. She asked her aunt if she had experienced that type of treatment, and her aunt recalled not having to endure any harm from the same family. She is aware that her salary has remained lower than that of the other household staff who work fewer hours. She started with a wage of THB 13,000 (US$ 400) per month (this is above minimum wage, but, when unpaid overtime work is accounted for, wages for domestic workers can be less than minimum wage). When she asked for THB 20,000 (US$ 617), she was offered THB 17,000 (US$ 525) per month. At the end of 2024 her salary was increased to THB 18,000 (US$ 555). Her salary is also often delayed and is handed out in installments instead of the agreed-upon monthly payment. And while she lives within her employer’s accommodation, her food and medical treatment are out of pocket. When she needed to treat a severe ear infection which cost THB 6,000 (US$ 185), and she asked for financial assistance, her employer handed her THB 1,000 (US$ 30) while she shouldered the rest.

Fearing the Lack of Opportunities for Fair Work Conditions

She secured a “Pink Card”, an official identification card provided to migrant workers from Myanmar, Cambodia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, and Viet Nam who entered Thailand irregularly. On top of this she needs to renew her work permit every two years and pay for government health insurance. She also sends remittances to her mother in Myanmar. She still has fear and shame due to how she perceives herself to be a burden because of her disability. She rarely goes outside the house to socialise, even during her two days of rest a month. And while she has joined a domestic workers’ association, and is much more aware of her rights, she feels she cannot change her current employer as she believes no one would hire her because of her disability.

Mathida Win’s silent suffering in the confines of her employer’s household highlights the lack of protections for migrant workers with disabilities who endure internalised stigma that results in further self-isolation and abuse. These situations call for the stronger reinforcement of not only safe and fair work conditions, but also of accessible grievance mechanisms to aid them whenever abuse ensues.

Images generated with assistance of OpenAI, images conceptualized and final edit by Ferdinand Paraan Jr.