Written by Chay Bacani-Florencio

Ma Nanda Khin is a 29-year-old Myanmar national with a hearing disability. She worked in her home country for nine years on a local sign language project run by a foreign university. However, when the project abruptly came to a stop, it left her unemployed. And while amid an unstable political situation that posed a significant threat of arrest and detention, particularly to young people like her 20-year-old brother, the safety of her family is also her primary concern. Looking to secure a better future for herself and her family, Nanda decided to move to Thailand to look for work, where her Thai friends with hearing disabilities also reside and where she hopes to fulfil her dream of building a beauty and fashion business.

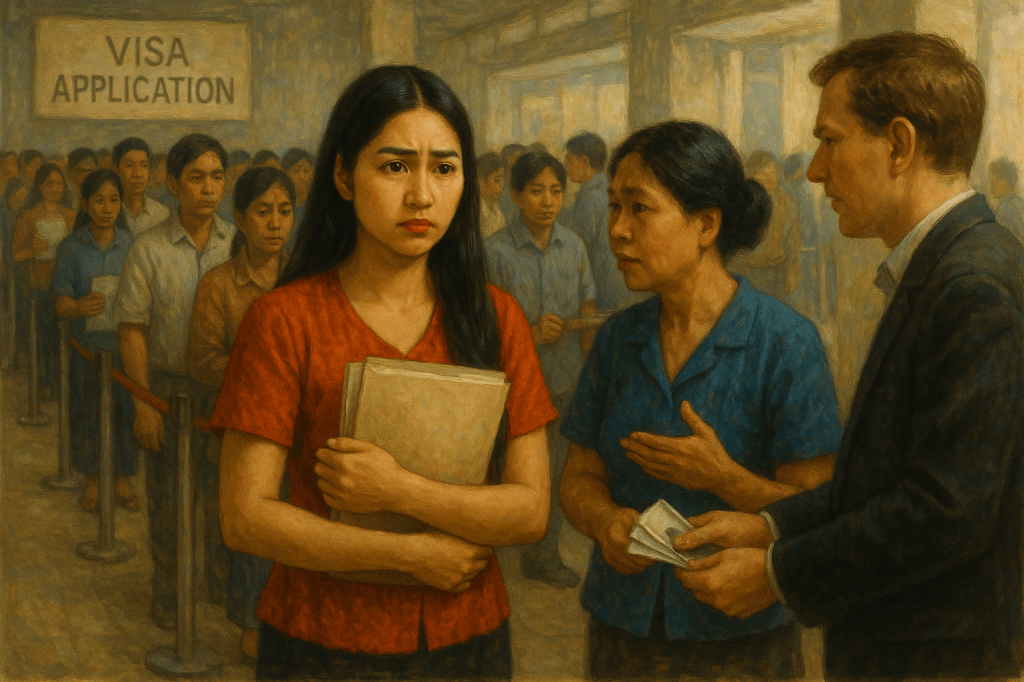

Bureaucratic Hurdles as Barriers to Migration

Not without any challenges, Ma Nanda was compelled to plead for her mother’s approval, as her mother felt deep concern about her daughter’s safety while travelling and adjusting to an unfamiliar country alone. She was able to reassure her mother by pointing out her previous experience travelling outside Myanmar. However, bureaucratic hurdles added to the barriers to a more stable life abroad. In Myanmar, long visa application queues gave her the impression that she is competing with other applicants who may be chosen over those like her who have disabilities. While at the Thai embassy in Yangon, Ma Nanda did not have access to a Sign Language Interpreter (SLI) to support her during the application process. Because of this gap, her mother had to step in and, wanting to help her daughter secure employment abroad, turned to a private broker to assist with processing the travel documents. This, in turn, required an anticipated additional MMK 150,000 (US$ 72) as a charge for their fees, which would prove to be a financial burden.

The Precarious State of Employment Opportunities Abroad

On July 25, 2024, when Ma Nanda Khin was finally able to migrate to Thailand, she soon found out that the domestic work job opportunity that she applied for was rejected. She suspects that upon learning of her disability, her employers rejected her. The experience was deeply discouraging and gave her anxiety. Her Thailand-based friends encouraged her to remain optimistic amid the challenges. She was also advised by the head of a Thai Organisation of Persons with Disabilities (OPD) to apply for jobs in person rather than online so that she would yield faster results. Still, she anticipates challenges, such as competing with applicants without disabilities and the financial burden of travelling for in-person job applications, which she may lose out to other applicants without disabilities.

Taking Up Space in the Midst of Uncertainty

Ma Nanda Khin was undeterred and actively sought new avenues for success. Looking to capitalize on her passion for retail and modelling, she looked into developing an e-commerce business selling beauty products and fashion, with a focus on traditional costumes.

Through all this, Ma Nanda Khin was made aware of the need to understand Thai law and practices. She heard from her Thai friends that having a disability card in Thailand would grant her access to services for persons with disabilities, which was more than she expected to receive back home. She was wrongfully made informed that the Thai government could readily provide her with free SLI service for persons with disabilities like her, under the Persons with Disabilities Empowerment Act, B.E. 2550 (2007) and its Amendment 2013 (Vol.2), that which would significantly ease her job search. However, Ma Nanda Khin likely remains unable to access these services, as she is a non-citizen looking for work. Typically, only Thai citizens and residents who underwent national registration are entitled to a disability card and its associated benefits.

This uncertainty exposes the gap between legal provisions and the realities faced by migrant workers with disabilities. For prospective deaf domestic workers, their households may lack the means to provide ongoing SLI, but the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) has made it clear – denying reasonable accommodation is discrimination. System-level solutions are needed. Governments and recruitment agencies must guarantee access to interpretation and communication support so that migrant workers with disabilities are not unfairly excluded from opportunities. A wider discussion is required about whether non-citizens with disabilities, who live, work and contribute, should also be able to access them.

Ma Nanda Khin was forced to flee not only due to political unrest but also limited job opportunities, Ma Nanda Khin experienced restrictive and inaccessible visa processes from her country of origin. And even with the assistance of a private broker for proper travel documentation, if employment in the country of destination is not assured, migrant workers like her are faced with the dangers not just of discriminatory acts in a foreign country but also of impoverishment. Inclusive hiring practices across countries should be ensured in all countries. Cross-border labour agreements backed by migration governance frameworks could play a role in safeguarding non-discrimination. And at the community level, a network for migrant workers with disabilities should be promoted and strengthened to make access to services and information timely and easily available to those in need.

Images generated with assistance of OpenAI, images conceptualized and final edit by Ferdinand Paraan Jr.