Written by Chay Bacani-Florencio

Ko Kyaw Min, a 33-year-old Myanmar national, migrated to Malaysia legally in 2009 with the assistance of a recruiter from Myanmar, on the prospect of a better life for himself and his family. Upon arrival in Penang, Malaysia, he worked for an automobile manufacturing company, fulfilling and even exceeding the one-year contract. After working unpaid overtime for one and a half years with his first employer, Ko Kyaw Min decided to take on another job washing cars to make ends meet and continue supporting his household in Myanmar. Unfortunately, his employer was also abusive in terms of time and wages. When he transitioned to working for an oil tanker, he was paid only 35 MYR (US$ 8.26) per day even though he was promised 45 MYR (US$ 10.62) per day. After confronting his manager about this, he made the decision to seek employment elsewhere. This is when he took on fixing ceilings as a private contractor.

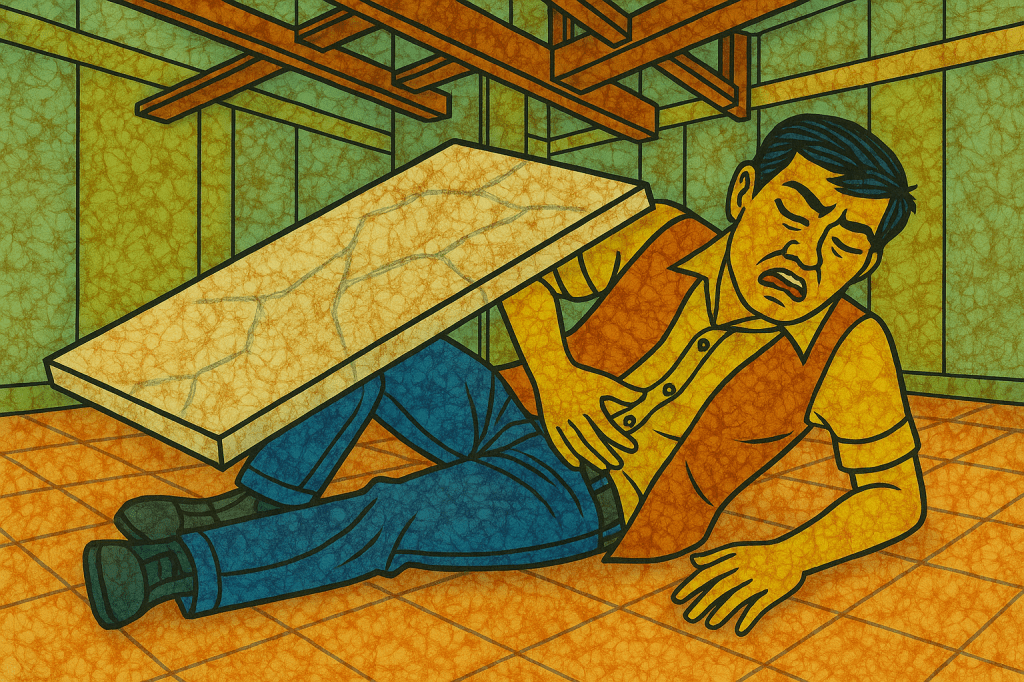

Workplace Injury and Lack of Employer Support

On June 15, 2012, just two months into his most recent employment, the ceiling board that he was repairing suddenly collapsed on him. Ko Kyaw Min’s friend called for an ambulance, and after about half an hour, it arrived and took him to a nearby hospital. The prognosis came. Ko Kyaw Min broke his backbone and needed surgery. He waited ten more days before he was transferred to another medical facility on the other side of Penang.

Ko Kyaw Min’s surgery, which doctors recommended could take two days, was delayed for 17 days due to lack of funds. A non-governmental organization (NGO) contributed 2,000 MYR (US$ 475) towards the surgery, while the rest of the 5,000 MYR (US$ 1,185) was covered by his family. His employer fled the scene and could not be located afterwards. He also did not receive any disability claim, benefits, or insurance coverage. His remaining wages, amounting to about 6,000 MYR (US$ 1,420), were also withheld by his employer. He was advised to file charges against his employer, but doing so required him to remain in Malaysia and personally appear in court. Bedridden from his recent operation, he prioritised returning home over pursuing legal action, as he had no means to support and care for himself. He felt he had no choice but to leave and get the required support from his family in Myanmar.

Ko Kyaw Min’s attempt to return to Myanmar was for him the most challenging part of his journey, which was further complicated by bureaucratic hurdles. Despite having a purchased plane ticket, he was denied boarding because he lacked a required recommendation letter from the Myanmar Embassy as his visa had expired. He spoke to the authorities, but the then-embassy officials did not show up at the airport as promised. With help from a friend, he stayed in Kuala Lumpur for five more days while continuing to plead for embassy documentation. Eventually, he was allowed to board after appealing directly to Malaysian immigration officials. Upon arrival in Myanmar, he was held and denied entry. A Burmese physician who had assisted him covered the fine, as Ko Kyaw Min had no means to do so.

Rehabilitation and Reintegration in Myanmar

When he returned to Myanmar, his stitches had become infected, requiring further treatment and a hospital stay of one month, followed by extended home recovery of two-three months. After eight to nine months, he then initiated his physical rehabilitation, which was five days a week and was paid for by his family. Ko Kyaw Min also received counselling and a computer training course from a Japanese vocational center – Association for Aid and Relief later on.

Having experienced multiple labour rights violations—including the denial of rightful compensation and employer abandonment —Ko Kyaw Min was unable to pursue justice due to his disability and lack of care and support in Malaysia. Despite this, he continues to aspire to work abroad to support his family, so long as he is employed by a fair and rights-respecting employer.

At the time of the interview, he was married to a fellow person with a disability, and together they are raising their five-year-old daughter. Despite his acquired disability, Ko Kyaw Min still fears the possibility of being conscripted into military service. Amid ongoing political unrest, he relies primarily on private institutions and NGOs for support, due to the absence of inclusive public services. His story serves as a powerful reminder that the processes of deployment abroad and return to one’s country of origin must be grounded in urgent, rights-based protections— with enforcement and redress transcending boundaries, ensuring that persons with disabilities are not left behind or exposed to further harm.

Images generated with assistance of OpenAI, images conceptualized and final edit by Ferdinand Paraan Jr.