Written by Chay Bacani-Florencio

Ko Hla Aung was only 15 years old when he migrated from Myanmar to Thailand in 2010. Like many young people from his country seeking to support their families, he took the journey without legal documents or a formal employment contract. He immediately found work as part of a fishing boat crew. While all crew members were also from Myanmar, they were undocumented and lived in constant fear of arrest or deportation by Thai immigration authorities. To avoid detection, they remained at sea for extended periods and slept on the floor of the boat.

From the Sea to Solitude

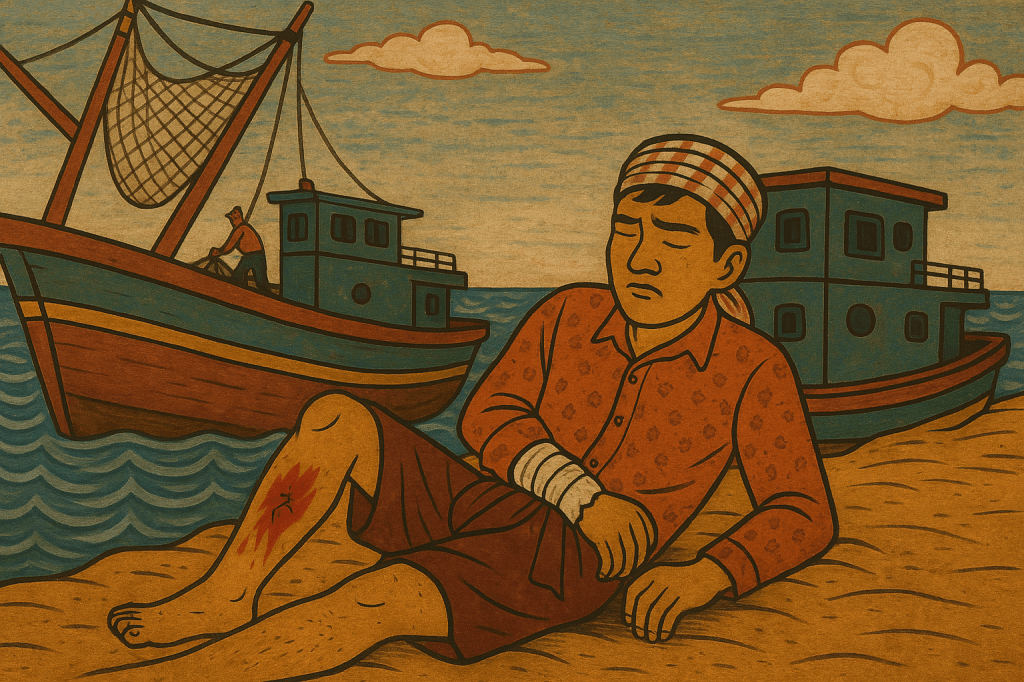

In 2012, at age 17, Ko Hla Aung sustained a life-altering injury when his trousers became entangled in the boat’s machinery. The accident resulted in a severe leg injury and a broken hand. He came back to shore and with the support of family members living in Thailand, he was taken on a six-hour journey by land to the nearest hospital. Due to the facility’s limitations, he was transferred to another hospital an hour away, where he underwent three operations that ultimately led to the amputation of his leg above the knee.

Ko Hla Aung remained in the hospital for one month and continued receiving medical care for nine months, including thrice-weekly physical rehabilitation. His employer covered all hospital expenses and provided financial support during his medical leave. He received a donated prosthesis through a hospital program. After a year of recovering, he went back to the fishing boat this time as the boat’s pilot in 2013. It was also around this time when he finally managed to procure his passport.

He recounted that his employer took measures to retain him in employment. He later had a new role, which came with a wage increase but less responsibilities. While this allowed him to spend more time alone, he felt that his employers were not too keen on giving difficult jobs to people with disabilities.

Ko Hla Aung was uncomfortable most of the time with how a part of Thailand’s community perceives persons with disabilities. He felt that he needed to understand how people view him instead of asking to be understood. It was only during his visits to the hospital to adjust and change his prosthesis that he was able to find and commune with other persons with disabilities.

Shifting Tides: Facing Adversity at Home

In 2016, Ko Hla Aung recalled a series of bombings in Thailand that made him consider returning to Myanmar for a short visit. However, after reflecting on his years spent abroad and enduring long hours at sea, he decided instead to remain in Myanmar and learn a new trade—mobile phone repair. At the time of the interview, he was running a small repair shop. Yet, despite rebuilding his livelihood, he continues to grapple with the psychological impact of acquiring a disability.

Back at home after the accident, Ko Hla Aung resorted to self-isolation, upon hearing how people told him he would no longer be capable of working or living independently because of his acquired disability. The internalized stigma led to his feelings of inferiority and episodes of depression. It is apparent to his experience how one’s psychological well-being also needed support and recovery during and even after hospitalization, as well as rehabilitation therapy.

Dignity After Disability

Ko Hla Aung’s experience reflects how intersecting factors and the absence of safe spaces for expressing grievances can lead to deep social isolation for persons with disabilities, even with a proper hospitalization and the experience of a supportive employer.

His story highlights how the psychological well-being of persons with disabilities is overlooked in post-disability care, and that sustained psychosocial support from the immediate community and the public sector is necessary to alleviate the emotional and mental toll of isolation, stigma, and lost livelihood.

Physical recovery, psychosocial counselling and the full participation of persons with disabilities must be supported as a matter of rights and dignity. These are essential to ensuring that migrant workers like Ko Hla Aung are respected and meaningfully included in their communities, whether in their home countries or abroad.

Images generated with assistance of OpenAI, images conceptualized and final edit by Ferdinand Paraan Jr.