Written by Chay Bacani-Florencio

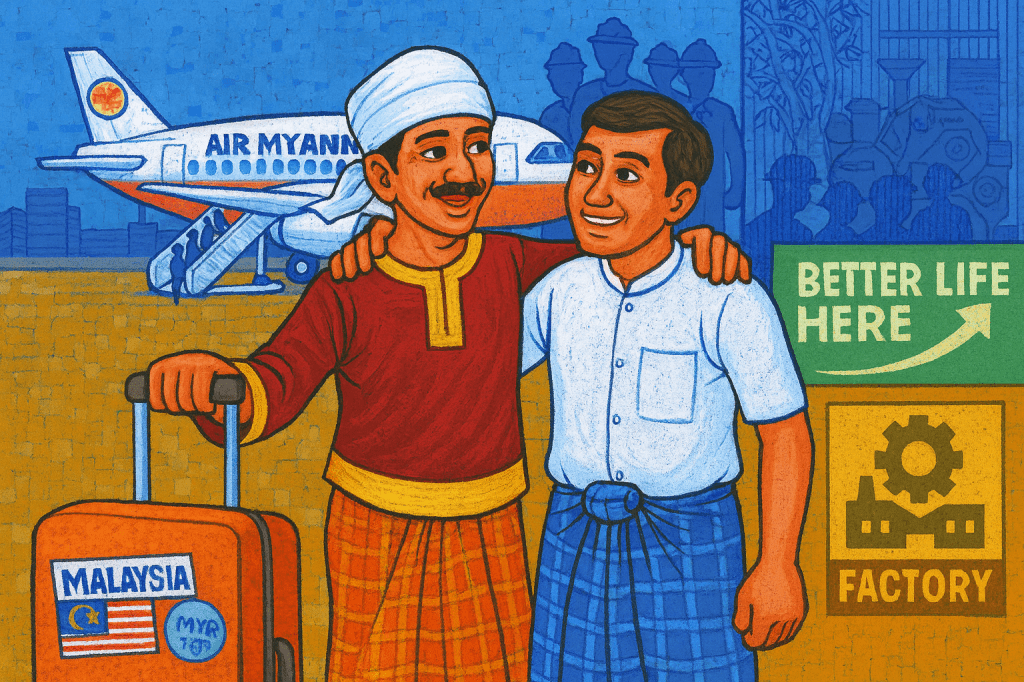

Ko Aung Min is a 52-year-old Myanmar national, graduated with a college degree, is married, and has two daughters. He aspired to work abroad to better provide for his family. In May 2001, with the help of his uncle, who served as his agent, he secured a single-entry visa for MYR 300,000 (US$ 92) to Malaysia and was employed within a month of migrating. He signed a contract with a factory that manufactures machine parts for heavy construction vehicles and machines. Usual work time for him was six days a week, and eight hours per day. He and his co-workers also opt to take on Sunday duty to be able to access double pay overtime, adding around MYR 900 (US$ 210) a month to their contracted wages.

Workplace Accident and Disability Onset

In May 2004, while operating a crane that suddenly broke, he asked for assistance from a co-worker to resolve the machine’s issue. While focused on the task at hand, another crane crashed into them, and Ko Aung Min fell from his seat on the crane. He was rushed to the hospital and was found to have broken his spine, which resulted in his paralysis from the waist down. He needed a major operation to have metal implants installed.

Ko Aung Min remained in the hospital for a month for surgery recovery. He was advised to do physical exercises as part of his rehabilitation. The factory owner paid for his bills only because the recruiter pressured the employer. While he received wages during his stay in the hospital, he was left without formal support upon discharge, except for an allowance of US$ 100 and a wheelchair. He had to stay at a friend’s house and survive through the help of his housemates, who prepared and left him with food, and assisted him to the bathroom only when they were back home. A bottle was within reach for when he needed to urinate once everyone left for work.

The Lack of Livelihood and Long Delay of Insurance Claims Upon Return Home

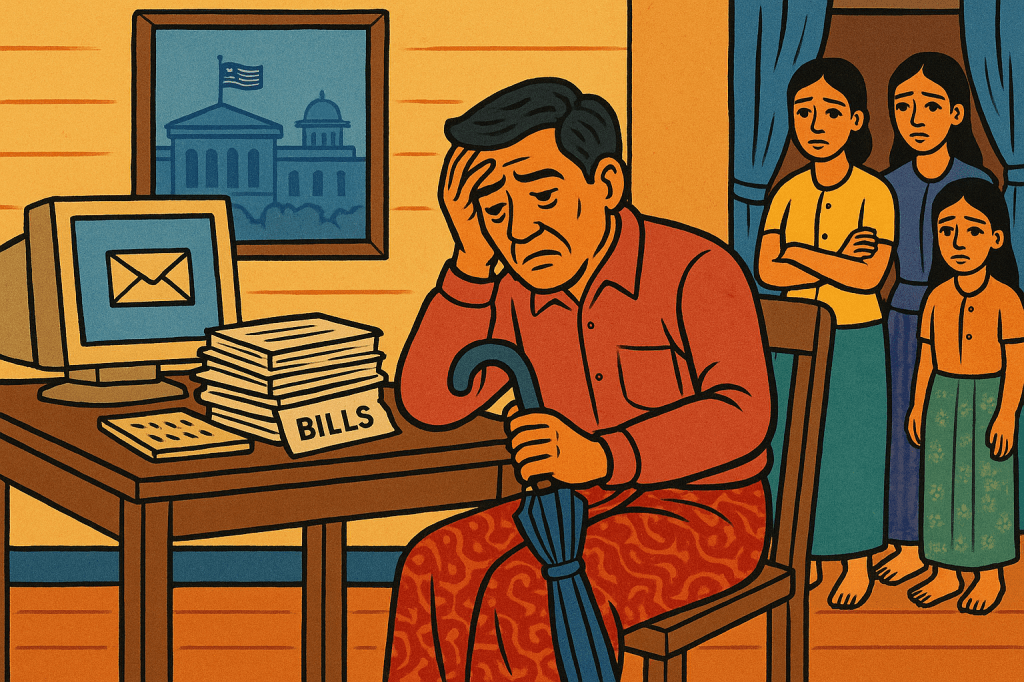

Without any prospect of being rehired or offered other job opportunities, Ko Aung Min’s employer provided his return ticket home. As he couldn’t survive on his own, he had to wait for a friend who would also return to Myanmar to assist him as necessary. Once back, he initially stayed at home for 2 weeks and went to a hospital’s rehabilitation center every day for six months. He regained mobility on one leg, was able to stand up on his own, and walk with an assistive device. Embarrassed by how people would perceive him having a disability, he preferred not to walk with a cane and used an umbrella instead to conceal his difficulty in mobility.

As part of his contract and mandated by the Malaysian government, he was entitled to claim life insurance compensation. However, Ko Aung Min waited eight years for the payment. Even with his incessant emails and follow-ups to the Malaysian embassy in Myanmar, it took his former employer to visit him and intervene upon discovering that he hadn’t received any of his insurance claims. Eventually, he was awarded MYR 27,000 (US$ 6,400), which amounts to two years’ worth of his wages. By the time he received it, half of it went to repaying debts that he had accumulated for his rehabilitation and daily living expenses. He invested what was left in his sister’s basket-weaving business. By 2010, he had a job as a salesperson in a shop. He remembers being unemployed as one of the lowest points of his life, having to rely on his parents not just for his hospital and rehabilitation bills, but also for his slightest needs and requests.

Reintegration Support as Part of Rehabilitation

The story of Ko Aung Min calls for the urgent need to protect the rights of migrant workers with disabilities while both abroad and at home. The systemic failure to provide for timely and accessible insurance payouts would have saved him years-long delays, financial burden of interest on debt repayment, and missed opportunities. And while his employer covered hospitalisation, employer accountability measures did not cover proper workplace accommodations, rehabilitation towards recovery, and reintegration. Once back to the community, a recovering person with disability should also be entitled to psychosocial counselling, where they should be given the necessary mental health support to combat isolation and despair.

Despite the accessibility of information through the modern technology of the internet and connectivity, migrant workers with acquired disabilities are still left in the dark about existing government mechanisms and services towards their protection. Comprehensive education on their rights is a cornerstone for their dignified living, inclusive participation, and successful reintegration in society.

Images generated with assistance of OpenAI, images conceptualized and final edit by Ferdinand Paraan Jr.