Written by Chay Bacani-Florencio

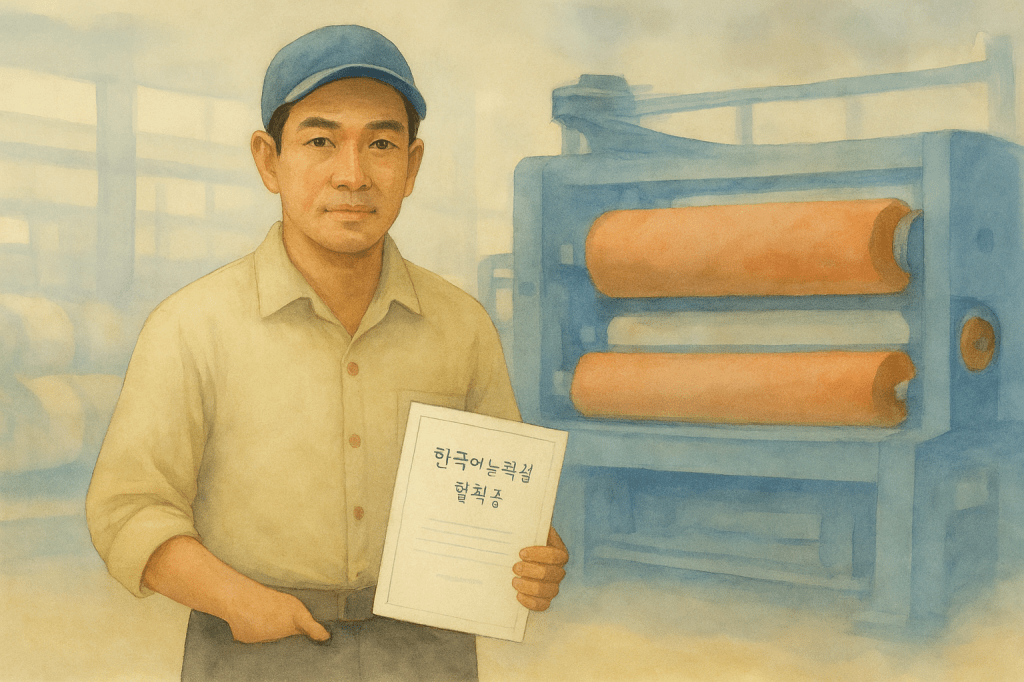

Channara Bun, a 33-year-old Cambodian, completed high school then decided to work abroad for better wages, knowing that degree holders in Cambodia do not earn enough locally. He took a Korean language exam in 2011 and migrated to the Republic of Korea in 2013, borrowing money from his family to cover the costs of his passport, visa application, and airfare.

Working in a textile manufacturing factory there, Channara Bun voluntarily worked 12-hour days, seven days a week, only taking days off during the two national holidays when the factory was non-operational. Working non-stop, despite the risk of exhaustion, was the only way by which he thought that he could secure his future financially. In 2017, a fabric he was working on got stuck in a 10-ton textile flattening machine nearby. He attempted to dislodge it using a metal brush, but when he failed, he reached for the fabric with his left hand, and it too got caught. Using his right hand, several fingers became trapped as well. He was still able to pull himself away just in time, before narrowly escaping being dragged entirely into the machine. Seeing the severity of his injury, his co-workers sought urgent care for him at a large hospital that is an hour away from the factory.

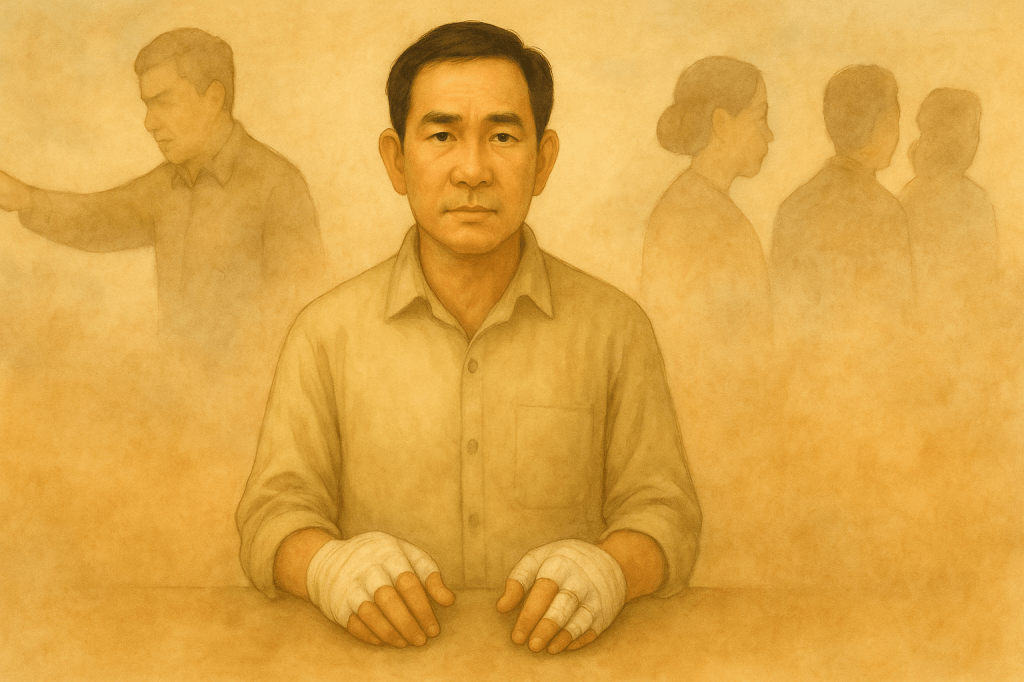

Channara Bun had surgery to implant metal rods in his fingers. Initially, he was given full assistance by the staff, as both of his hands were severely injured. Later on, the support dwindled, and he had to rely on random strangers who volunteered to help him use the restroom and get back to his bed. This went on for seven months.

Half of the payment for his treatment and hospitalization came from the Republic of Korea government-mandated health insurance, deducted from his wages, while the remaining half was shouldered by the factory owner. Except for during his major surgery, in which the hospital provided a language interpreter, he was not informed of his treatment details, including his physical therapy and laser procedure for his wounds. During his confinement, a Cambodian friend living in the Republic of Korea helped connect him to an organisation that provided a one-time donation of US$ 200 and a fruit basket that was personally delivered to his hospital room.

Discarded and Dispossessed After Injury

Channara Bun, together with the help of a friend, was able to secure legal representation and initiate a compensation claim as the injury was sustained during work hours. His employer did not adhere to their demands. He obtained a little beyond US$ 10,000, which is equivalent to one year’s worth of wages, and his one-month back pay. He did not receive payment while confined, and when they appealed for reinvestigation, the factory owner did not cooperate and rejected the demands for higher recompense.

As his employment contract and work visa expire every four years, without any hopes of being rehired in the same factory and elsewhere, Channara Bun needed to fly back to Cambodia. He believed that foreign persons with disabilities were not permitted to work in Korea. While there appears to be no clear legal precedent or official restriction confirming this, the lack of protection means that employer preferences often act as a de facto barrier. Since employers hold the power to decide on visa extensions, many simply replace workers with someone ‘younger’ and ‘healthier’ leaving persons with disabilities at a disadvantage.

He had to pay for his flight home and start his life without any support from a reintegration programme, nor further physical and psycho-social therapy from the government. He has not applied for a disability card, has yet to be employed, and is now faced with limited physical functionality of his hands post-injury, as well as memory problems and bouts of depression from time to time.

The Unseen Costs of Disability Acquired in Unsafe Workplaces

Channara Bun opened the possibility of asking for additional compensation from his former employer, but the transportation fees back to the Republic of Korea to personally attend the legal proceedings would result in further financial loss, which he felt was not worth the risk. Living off only his savings, he attempted to support his wife and daughter. But, since his father-in-law deemed him unfit to provide because of his disability, his first marriage ended due to the stigma around his disability. He has since remarried and aspires to return to work in the Republic of Korea, citing the challenges in obtaining a job that sufficiently supports a family in Cambodia.

Workplace accidents caused by the absence of basic occupational safety protections commonly result in permanent impairment that has life-long consequences, such as economic hardship, social stigma, and even unemployment. Additionally, worker fatigue due to a non-stop schedule increases likelihood of injury. This is a dangerous precedent to allow for migrant workers who feel compelled to maximise their earnings. Adequate social protections through reintegration support, including disability registration and vocational retraining, are necessary for migrant workers with disabilities, as illustrated in Channara Bun’s story of how not only machines but also social systems are life-altering and unforgiving.

Images generated with assistance of OpenAI, images conceptualized and final edit by Ferdinand Paraan Jr.